But first, a little bit of context

Traditionally, High-Performance Computing clusters face a challenge when dealing with modern, data-intensive applications. Existing HPC storage systems, long designed with spinning disks to provide efficient and parallel sequential read/write operations, often become bottlenecks for modern workloads generated by AI/ML or CryoEM applications. Those demand substantial data storage and processing capabilities, putting a strain on traditional systems.

So to accommodate those new needs and future evolution of the HPC I/O landscape, we at Stanford Research Computing, with the generous support of the Vice Provost and Dean of Research, have been hard at work for over two years, revamping Sherlock's scratch with an all-flash system.

And it was not just a matter of taking delivery of a new turn-key system. As most things we do, it was done entirely in-house: from the original vendor-agnostic design, upgrade plan, budget requests, procurement, gradual in-place hardware replacement at the Stanford Research Computing Facility (SRCF), deployment and validation, performance benchmarks, to the final production stages, all of those steps were performed with minimum disruption for all Sherlock users.

The technical details

The /scratch file system on Sherlock is using Lustre, an open-source, parallel file system that supports many requirements of leadership class HPC environments. And as you probably know by now, Stanford Research Computing loves open source! We actively contribute to the Lustre community and are a proud member of OpenSFS, a non-profit industry organization that supports vendor-neutral development and promotion of Lustre.

In Lustre, file metadata and data are stored separately, with Object Storage Servers (OSS) serving file data on the network. Each OSS pair and associated storage devices forms an I/O cell, and Sherlock's scratch has just bid farewell to its old HDD-based I/O cells. In their place, new flash-based I/O cells have taken the stage, each equipped with 96 x 15.35TB SSDs, delivering mind-blowing performance.

Sherlock’s /scratch has 8 I/O cells and the goal was to replace every one of them. Our new I/O cell has 2 OSS with Infiniband HDR at 200Gb/s (or 25GB/s) connected to 4 storage chassis, each with 24 x 15.35TB SSD (dual-attached 12Gb/s SAS), as pictured below:

Of course, you can’t just replace each individual rotating hard-drive with a SSD, there are some infrastructure changes required, and some reconfiguration needed. The upgrade, executed between January 2023 and January 2024, was a seamless transition. Old HDD-based I/O cells were gracefully retired, one by one, while flash-based ones progressively replaced them, gradually boosting performance for all Sherlock users throughout the year.

All of those replacements happened while the file system was up and running, serving data to the thousands of computing jobs that run on Sherlock every day. Driven by our commitment to minimize disruptions to users, our top priority was to ensure uninterrupted access to data throughout the upgrade. Data migration is never fun, and we wanted to avoid having to ask users to manually transfer their files to a new, separate storage system. This is why we developed and contributed a new feature in Lustre, which allowed us to seamlessly remove existing storage devices from the file system, before the new flash drives could be added. More technical details about the upgrade have been presented during the LAD’22 conference.

Today, we are happy to announce that the upgrade is officially complete, and Sherlock stands proud with a whopping 9,824 TB of solid-state storage in production. No more spinning disks in sight!

Key benefits

For users, the immediately visible benefits are quicker access to their files, faster data transfers, shorter job execution times for I/O intensive applications. More specifically, every key metric has been improved:

IOPS: over 100x (results may vary, see below)

Backend bandwidth: 6x (128 GB/s to 768 GB/s)

Frontend bandwidth: 2x (200 GB/s to 400 GB/s)

Usable volume: 1.6x (6.1 PB to 9.8 PB)

In terms of measured improvement, the graph below shows the impact of moving to full-flash storage for reading data from 1, 8 and 16 compute nodes, compared to the previous /scratch file system:

And we even tried to replicate the I/O patterns of AlphaFold, a well-known AI model to predict protein structure, and the benefits are quite significant, with up to 125x speedups in some cases:

This upgrade is a major improvement that will benefit all Sherlock users, and Sherlock’s enhanced I/O capabilities will allow them to approach data-intensive tasks with unprecedented efficiency. We hope it will help support the ever-increasing computing needs of the Stanford research community, and enable even more breakthroughs and discoveries.

As usual, if you have any question or comment, please don’t hesitate to reach out to Research Computing at [email protected]. 🚀🔧

But first, a little bit of context

Traditionally, High-Performance Computing clusters face a challenge when dealing with modern, data-intensive applications. Existing HPC storage systems, long designed with spinning disks to provide efficient and parallel sequential read/write operations, often become bottlenecks for modern workloads generated by AI/ML or CryoEM applications. Those demand substantial data storage and processing capabilities, putting a strain on traditional systems.

So to accommodate those new needs and future evolution of the HPC I/O landscape, we at Stanford Research Computing, with the generous support of the Vice Provost and Dean of Research, have been hard at work for over two years, revamping Sherlock's scratch with an all-flash system.

And it was not just a matter of taking delivery of a new turn-key system. As most things we do, it was done entirely in-house: from the original vendor-agnostic design, upgrade plan, budget requests, procurement, gradual in-place hardware replacement at the Stanford Research Computing Facility (SRCF), deployment and validation, performance benchmarks, to the final production stages, all of those steps were performed with minimum disruption for all Sherlock users.

The technical details

The /scratch file system on Sherlock is using Lustre, an open-source, parallel file system that supports many requirements of leadership class HPC environments. And as you probably know by now, Stanford Research Computing loves open source! We actively contribute to the Lustre community and are a proud member of OpenSFS, a non-profit industry organization that supports vendor-neutral development and promotion of Lustre.

In Lustre, file metadata and data are stored separately, with Object Storage Servers (OSS) serving file data on the network. Each OSS pair and associated storage devices forms an I/O cell, and Sherlock's scratch has just bid farewell to its old HDD-based I/O cells. In their place, new flash-based I/O cells have taken the stage, each equipped with 96 x 15.35TB SSDs, delivering mind-blowing performance.

Sherlock’s /scratch has 8 I/O cells and the goal was to replace every one of them. Our new I/O cell has 2 OSS with Infiniband HDR at 200Gb/s (or 25GB/s) connected to 4 storage chassis, each with 24 x 15.35TB SSD (dual-attached 12Gb/s SAS), as pictured below:

Of course, you can’t just replace each individual rotating hard-drive with a SSD, there are some infrastructure changes required, and some reconfiguration needed. The upgrade, executed between January 2023 and January 2024, was a seamless transition. Old HDD-based I/O cells were gracefully retired, one by one, while flash-based ones progressively replaced them, gradually boosting performance for all Sherlock users throughout the year.

All of those replacements happened while the file system was up and running, serving data to the thousands of computing jobs that run on Sherlock every day. Driven by our commitment to minimize disruptions to users, our top priority was to ensure uninterrupted access to data throughout the upgrade. Data migration is never fun, and we wanted to avoid having to ask users to manually transfer their files to a new, separate storage system. This is why we developed and contributed a new feature in Lustre, which allowed us to seamlessly remove existing storage devices from the file system, before the new flash drives could be added. More technical details about the upgrade have been presented during the LAD’22 conference.

Today, we are happy to announce that the upgrade is officially complete, and Sherlock stands proud with a whopping 9,824 TB of solid-state storage in production. No more spinning disks in sight!

Key benefits

For users, the immediately visible benefits are quicker access to their files, faster data transfers, shorter job execution times for I/O intensive applications. More specifically, every key metric has been improved:

IOPS: over 100x (results may vary, see below)

Backend bandwidth: 6x (128 GB/s to 768 GB/s)

Frontend bandwidth: 2x (200 GB/s to 400 GB/s)

Usable volume: 1.6x (6.1 PB to 9.8 PB)

In terms of measured improvement, the graph below shows the impact of moving to full-flash storage for reading data from 1, 8 and 16 compute nodes, compared to the previous /scratch file system:

And we even tried to replicate the I/O patterns of AlphaFold, a well-known AI model to predict protein structure, and the benefits are quite significant, with up to 125x speedups in some cases:

This upgrade is a major improvement that will benefit all Sherlock users, and Sherlock’s enhanced I/O capabilities will allow them to approach data-intensive tasks with unprecedented efficiency. We hope it will help support the ever-increasing computing needs of the Stanford research community, and enable even more breakthroughs and discoveries.

As usual, if you have any question or comment, please don’t hesitate to reach out to Research Computing at [email protected]. 🚀🔧

normal partition on Sherlock is getting an upgrade!With the addition of 24 brand new SH3_CBASE.1 compute nodes, each featuring one AMD EPYC 7543 Milan 32-core CPU and 256 GB of RAM, Sherlock users now have 768 more CPU cores at there disposal. Those new nodes will complete the existing 154 compute nodes and 4,032 core in that partition, for a new total of 178 nodes and 4,800 CPU cores.

The

normal partition is Sherlock’s shared pool of compute nodes, which is available free of charge to all Stanford Faculty members and their research teams, to support their wide range of computing needs. In addition to this free set of computing resources, Faculty can supplement these shared nodes by purchasing additional compute nodes, and become Sherlock owners. By investing in the cluster, PI groups not only receive exclusive access to the nodes they purchased, but also get access to all of the other owner compute nodes when they're not in use, thus giving them access to the whole breadth of Sherlock resources, currently over over 1,500 compute nodes, 46,000 CPU cores and close to 4 PFLOPS of computing power.

We hope that this new expansion of the

normal partition, made possible thanks to additional funding provided by the University Budget Group as part of the FY23 budget cycle, will help support the ever-increasing computing needs of the Stanford research community, and enable even more breakthroughs and discoveries.As usual, if you have any question or comment, please don’t hesitate to reach out at [email protected].

]]>

normal partition on Sherlock is getting an upgrade!With the addition of 24 brand new SH3_CBASE.1 compute nodes, each featuring one AMD EPYC 7543 Milan 32-core CPU and 256 GB of RAM, Sherlock users now have 768 more CPU cores at there disposal. Those new nodes will complete the existing 154 compute nodes and 4,032 core in that partition, for a new total of 178 nodes and 4,800 CPU cores.

The

normal partition is Sherlock’s shared pool of compute nodes, which is available free of charge to all Stanford Faculty members and their research teams, to support their wide range of computing needs. In addition to this free set of computing resources, Faculty can supplement these shared nodes by purchasing additional compute nodes, and become Sherlock owners. By investing in the cluster, PI groups not only receive exclusive access to the nodes they purchased, but also get access to all of the other owner compute nodes when they're not in use, thus giving them access to the whole breadth of Sherlock resources, currently over over 1,500 compute nodes, 46,000 CPU cores and close to 4 PFLOPS of computing power.

We hope that this new expansion of the

normal partition, made possible thanks to additional funding provided by the University Budget Group as part of the FY23 budget cycle, will help support the ever-increasing computing needs of the Stanford research community, and enable even more breakthroughs and discoveries.As usual, if you have any question or comment, please don’t hesitate to reach out at [email protected].

]]>

So today, we’re introducing a new Sherlock catalog refresh, a Sherlock 3.5 of sorts.

The new catalog

So, what changes? What stays the same?

In a nutshell, you’ll continue to be able to purchase the existing node types that you’re already familiar with:

CPU configurations:

CBASE: base configuration ($)CPERF: high core-count configuration ($$)CBIGMEM: large-memory configuration ($$$$)

GPU configurations

G4FP32: base GPU configuration ($$)G4TF64: HPC GPU configuration ($$$)G8TF64: best-in-class GPU configuration ($$$$)

But they now come with better and faster components!

To avoid confusion, the configuration names in the catalog will be suffixed with a index to indicate the generational refresh, but will keep the same global denomination. For instance, the previous SH3_CBASE configuration is now replaced with a SH3_CBASE.1 configuration that still offers 32 CPU cores and 256 GB of RAM.

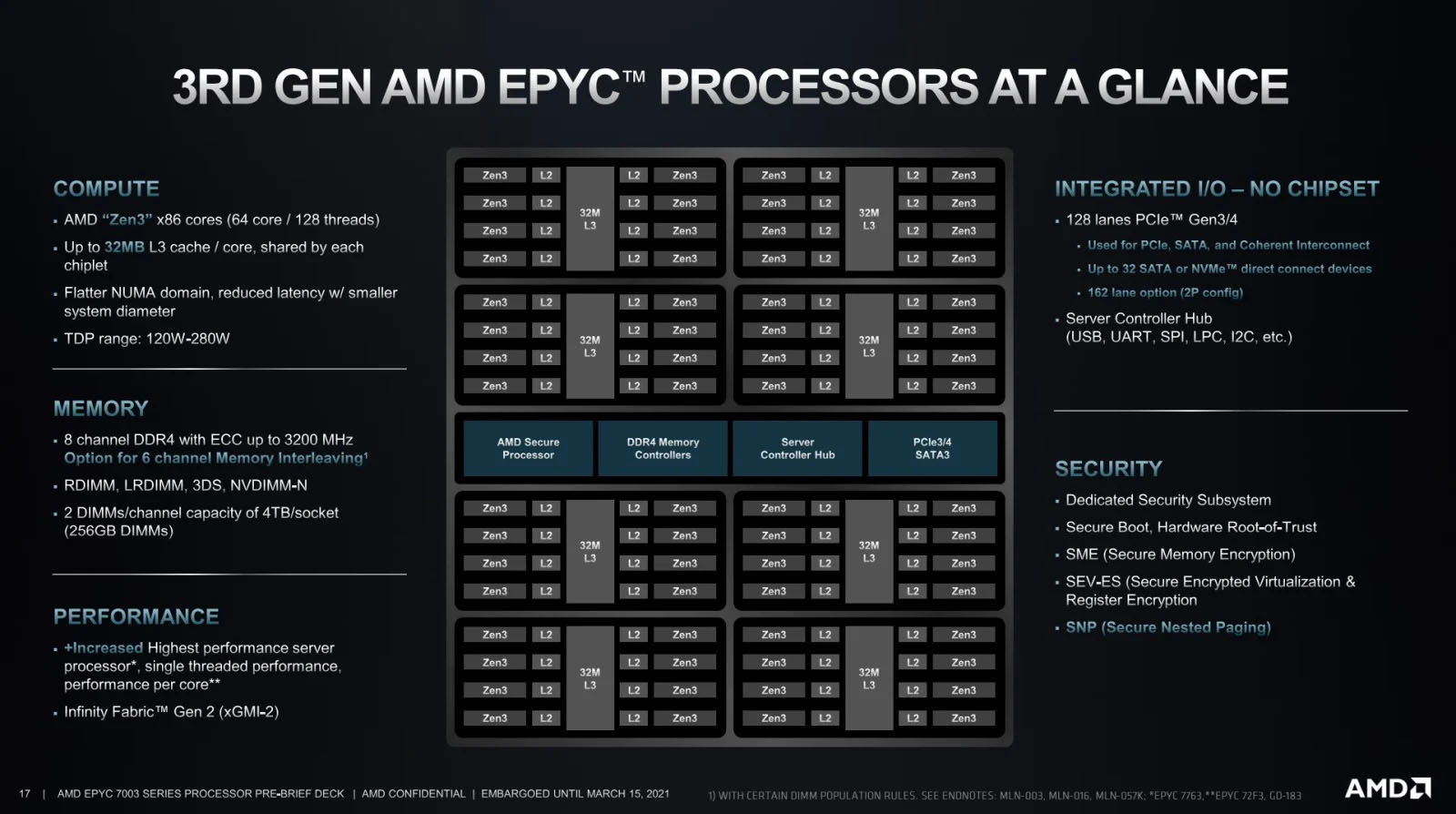

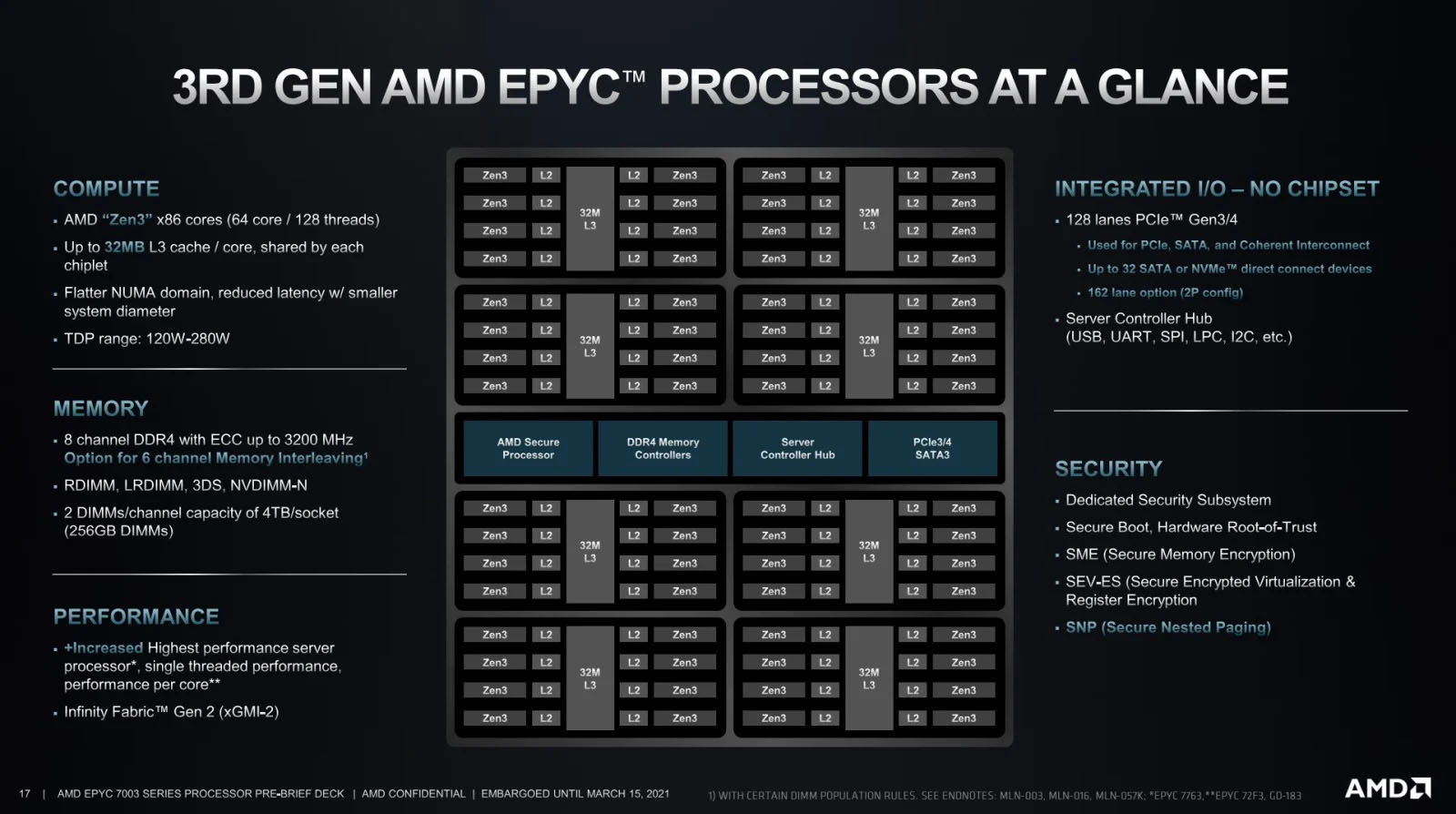

A new CPU generation

The main change in the existing configuration is the introduction of the new AMD 3rd Gen EPYC Milan CPUs. In addition to the advantages of the previous Rome CPUs, this new generation brings:

a new micro-architecture (Zen3)

a ~20% performance increase in instructions completed per clock cycle (IPC)

enhanced memory performance, with a unified 32 MB L3 cache

improved CPU clock speeds

More specifically, for Sherlock, the following CPU models are now used:

Model | Sherlock 3.0 (Rome) | Sherlock 3.5 (Milan) |

|---|---|---|

| 1× 7502 (32-core, 2.50GHz) | 1× 7543 (32-core, 2.75GHz) |

| 2× 7742 (64-core, 2.25GHz) | 2× 7763 (64-core, 2.45GHz) |

| 2× 7502 (32-core, 2.50GHz) | 2× 7543 (32-core, 2.75GHz) |

| 1× 7502 (32-core, 2.50GHz) | 1× 7543 (32-core, 2.75GHz) |

| 2× 7502 (32-core, 2.50GHz) | 2× 7543 (32-core, 2.75GHz) |

| 2× 7742 (64-core, 2.25GHz) | 2× 7763 (64-core, 2.45GHz) |

In addition to IPC and L3 cache improvements, the new CPUs also bring a frequency boost that will provide a substantial performance improvement.

New GPU options

On the GPU front, the two main changes are the re-introduction of the G4FP32 model, and the doubling of GPU memory all across the board.

GPU memory is quickly becoming the constraining factor for training deep-learning models that keep increasing in size. Having large amounts of GPU memory is now key for running medical imaging workflows, computer vision models, or anything that requires processing large images.

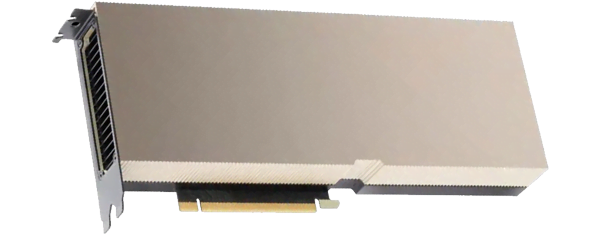

The entry-level G4FP32 model is back in the catalog, with a new NVIDIA A40 GPU in an updated SH3_G4FP32.2 configuration. The A40 GPU not only provides higher performance than the previous model it replaces, but it also comes with twice as much GPU memory, with a whopping 48GB of GDDR6.

The higher-end G4TF64 and G8TF64 models have also been updated with newer AMD CPUs, as well as updated versions of the NVIDIA A100 GPU, now each featuring a massive 80GB of HBM2e memory.

Get yours today!

For more details and pricing, please check out the Sherlock catalog (SUNet ID required).

If you’re interested in getting your own compute nodes on Sherlock, all the new configurations are available for purchase today, and can be ordered online though the Sherlock order form (SUNet ID required).

As usual, please don’t hesitate to reach out if you have any questions!

So today, we’re introducing a new Sherlock catalog refresh, a Sherlock 3.5 of sorts.

The new catalog

So, what changes? What stays the same?

In a nutshell, you’ll continue to be able to purchase the existing node types that you’re already familiar with:

CPU configurations:

CBASE: base configuration ($)CPERF: high core-count configuration ($$)CBIGMEM: large-memory configuration ($$$$)

GPU configurations

G4FP32: base GPU configuration ($$)G4TF64: HPC GPU configuration ($$$)G8TF64: best-in-class GPU configuration ($$$$)

But they now come with better and faster components!

To avoid confusion, the configuration names in the catalog will be suffixed with a index to indicate the generational refresh, but will keep the same global denomination. For instance, the previous SH3_CBASE configuration is now replaced with a SH3_CBASE.1 configuration that still offers 32 CPU cores and 256 GB of RAM.

A new CPU generation

The main change in the existing configuration is the introduction of the new AMD 3rd Gen EPYC Milan CPUs. In addition to the advantages of the previous Rome CPUs, this new generation brings:

a new micro-architecture (Zen3)

a ~20% performance increase in instructions completed per clock cycle (IPC)

enhanced memory performance, with a unified 32 MB L3 cache

improved CPU clock speeds

More specifically, for Sherlock, the following CPU models are now used:

Model | Sherlock 3.0 (Rome) | Sherlock 3.5 (Milan) |

|---|---|---|

| 1× 7502 (32-core, 2.50GHz) | 1× 7543 (32-core, 2.75GHz) |

| 2× 7742 (64-core, 2.25GHz) | 2× 7763 (64-core, 2.45GHz) |

| 2× 7502 (32-core, 2.50GHz) | 2× 7543 (32-core, 2.75GHz) |

| 1× 7502 (32-core, 2.50GHz) | 1× 7543 (32-core, 2.75GHz) |

| 2× 7502 (32-core, 2.50GHz) | 2× 7543 (32-core, 2.75GHz) |

| 2× 7742 (64-core, 2.25GHz) | 2× 7763 (64-core, 2.45GHz) |

In addition to IPC and L3 cache improvements, the new CPUs also bring a frequency boost that will provide a substantial performance improvement.

New GPU options

On the GPU front, the two main changes are the re-introduction of the G4FP32 model, and the doubling of GPU memory all across the board.

GPU memory is quickly becoming the constraining factor for training deep-learning models that keep increasing in size. Having large amounts of GPU memory is now key for running medical imaging workflows, computer vision models, or anything that requires processing large images.

The entry-level G4FP32 model is back in the catalog, with a new NVIDIA A40 GPU in an updated SH3_G4FP32.2 configuration. The A40 GPU not only provides higher performance than the previous model it replaces, but it also comes with twice as much GPU memory, with a whopping 48GB of GDDR6.

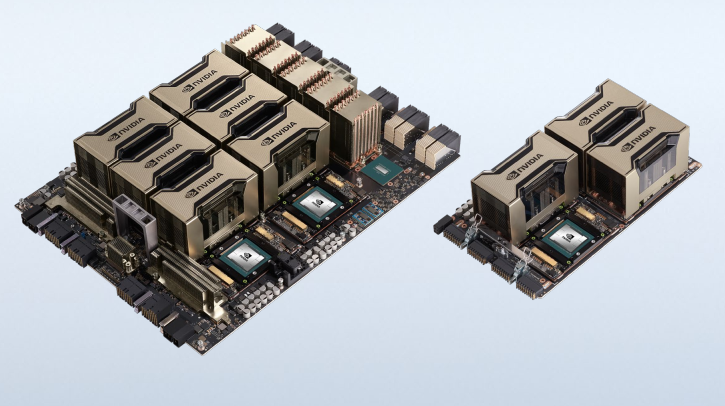

The higher-end G4TF64 and G8TF64 models have also been updated with newer AMD CPUs, as well as updated versions of the NVIDIA A100 GPU, now each featuring a massive 80GB of HBM2e memory.

Get yours today!

For more details and pricing, please check out the Sherlock catalog (SUNet ID required).

If you’re interested in getting your own compute nodes on Sherlock, all the new configurations are available for purchase today, and can be ordered online though the Sherlock order form (SUNet ID required).

As usual, please don’t hesitate to reach out if you have any questions!

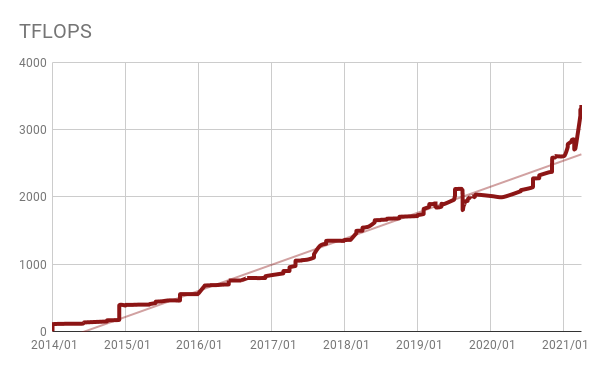

A significant expansion milestone

A few days ago, Sherlock has reached a major expansion milestone, largely owing to significant purchases from the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, but also thanks to multiple existing owner groups who decided to renew their investment in Sherlock by purchasing additional hardware.

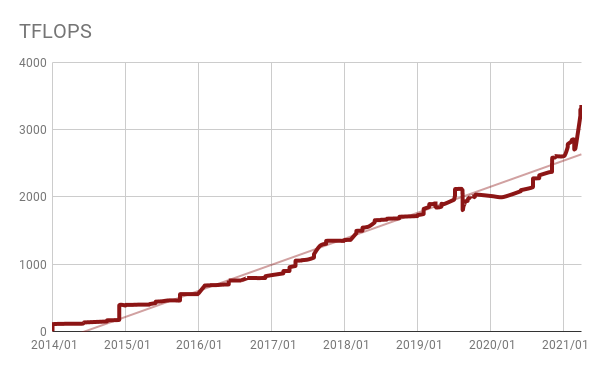

With these recent additions, Sherlock reached a theoretical power of over 3 Petaflops, 3 thousand million million (1015) floating-point operations per second. That would place it around the 150th position in the most recent TOP500 list of the most powerful computer systems in the world.

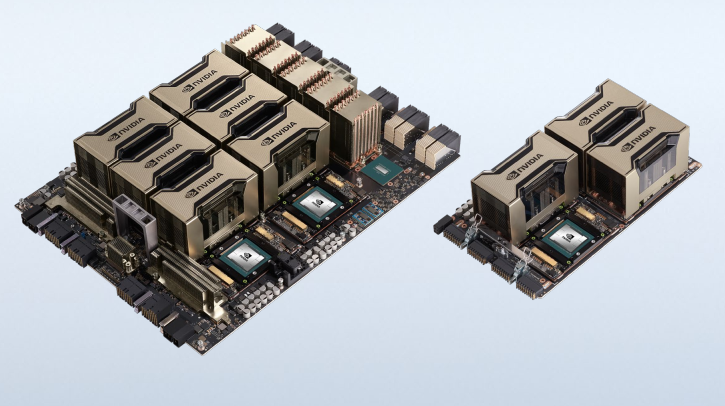

Among the newly added nodes, a number of SH3_G8TF64 nodes, each featuring 128 CPU cores, 1TB of RAM, 8x A100 SXM4 GPUs (NVLink) and two Infiniband HDR interfaces providing 400Gb/s of interconnect bandwidth, both for storage and inter-node communication. Those nodes alone provide over half a Petaflop of computing power.

Sherlock now features over 1,700 compute nodes, occupying 45 data-center racks, and consuming close to half a megawatt of power. Over 44,000 CPU cores, more than 120 Infiniband switches and close to 20 miles of cables help support the daily computing activities of over 5,000 users. For even more facts and numbers, checkout the Sherlock Facts page!

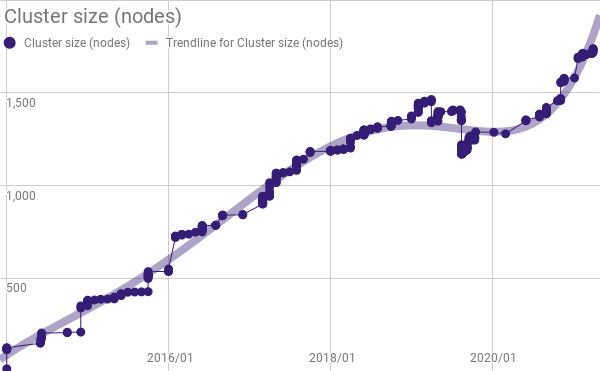

A steady growth

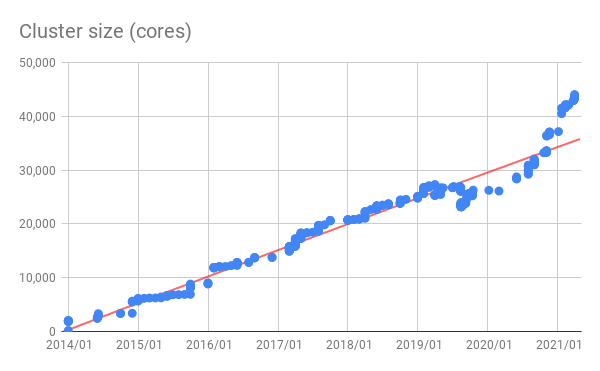

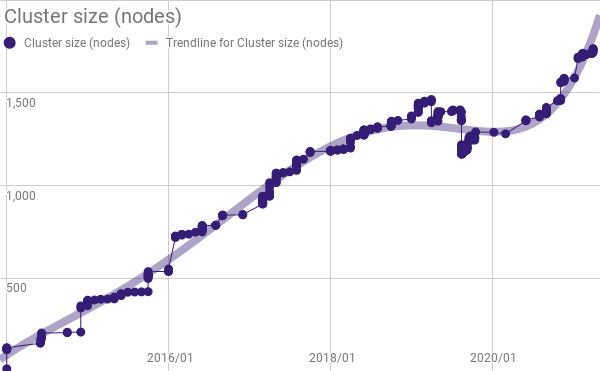

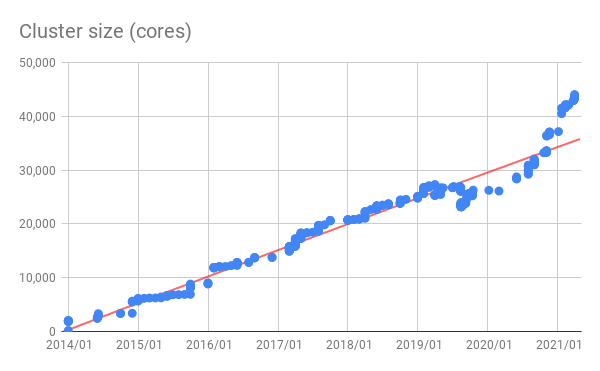

Since in first days in 2014, and its initial 120 nodes, Sherlock has been growing at a steady pace. Three generations and as many Infiniband fabrics later, and after a few months of slowdown at the beginning of 2020, expansion has resumed and is going stronger than ever:

|  |

The road ahead

To keep expanding Sherlock and continue to serve the computing needs of the Stanford research community, rack space used by first generation Sherlock nodes needs to be reclaimed to make room for the next generation. Those 1st-gen nodes have been running well over their initial service life of 4 years, and in most cases, we’ve even been able to keep them running for an extra year. But data-center space being the hot property it has now become, and since demand for new nodes is not exactly dwindling down, we’ll be starting to retire the older Sherlock nodes to accommodate the ever-increasing requests for more computing power. We’ve started working on renewal plans with those node owners, and the process is already underway.

So for a while, Sherlock will shrink in size, as old nodes are retired. Before it can start growing again!

Catalog changes

As we move forward, the Sherlock Compute Nodes Catalog is also evolving, to follow the latest technological trends, and to adapt to the computing needs of our research community.

As part of this evolution, the recently announced SH3_G4FP32 configuration is sadly not available anymore, as vendors suddenly and globally discontinued the consumer-grade GPU model that was powering this configuration. They don’t have plans to bring back anything comparable, so that configuration had to be pulled from the catalog, unfortunately.

On a more positive note, a significant and exciting catalog refresh is coming up, and will be announced soon. Stay tuned! 🤫

As usual, we want to sincerely thank every one of you, Sherlock users, for your patience when things break, your extraordinary motivation and your continuous support. We’re proud of supporting your amazing work, and Sherlock simply wouldn’t exist without you.

Happy computing and don’t hesitate to reach out if you have any questions!

A significant expansion milestone

A few days ago, Sherlock has reached a major expansion milestone, largely owing to significant purchases from the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, but also thanks to multiple existing owner groups who decided to renew their investment in Sherlock by purchasing additional hardware.

With these recent additions, Sherlock reached a theoretical power of over 3 Petaflops, 3 thousand million million (1015) floating-point operations per second. That would place it around the 150th position in the most recent TOP500 list of the most powerful computer systems in the world.

Among the newly added nodes, a number of SH3_G8TF64 nodes, each featuring 128 CPU cores, 1TB of RAM, 8x A100 SXM4 GPUs (NVLink) and two Infiniband HDR interfaces providing 400Gb/s of interconnect bandwidth, both for storage and inter-node communication. Those nodes alone provide over half a Petaflop of computing power.

Sherlock now features over 1,700 compute nodes, occupying 45 data-center racks, and consuming close to half a megawatt of power. Over 44,000 CPU cores, more than 120 Infiniband switches and close to 20 miles of cables help support the daily computing activities of over 5,000 users. For even more facts and numbers, checkout the Sherlock Facts page!

A steady growth

Since in first days in 2014, and its initial 120 nodes, Sherlock has been growing at a steady pace. Three generations and as many Infiniband fabrics later, and after a few months of slowdown at the beginning of 2020, expansion has resumed and is going stronger than ever:

|  |

The road ahead

To keep expanding Sherlock and continue to serve the computing needs of the Stanford research community, rack space used by first generation Sherlock nodes needs to be reclaimed to make room for the next generation. Those 1st-gen nodes have been running well over their initial service life of 4 years, and in most cases, we’ve even been able to keep them running for an extra year. But data-center space being the hot property it has now become, and since demand for new nodes is not exactly dwindling down, we’ll be starting to retire the older Sherlock nodes to accommodate the ever-increasing requests for more computing power. We’ve started working on renewal plans with those node owners, and the process is already underway.

So for a while, Sherlock will shrink in size, as old nodes are retired. Before it can start growing again!

Catalog changes

As we move forward, the Sherlock Compute Nodes Catalog is also evolving, to follow the latest technological trends, and to adapt to the computing needs of our research community.

As part of this evolution, the recently announced SH3_G4FP32 configuration is sadly not available anymore, as vendors suddenly and globally discontinued the consumer-grade GPU model that was powering this configuration. They don’t have plans to bring back anything comparable, so that configuration had to be pulled from the catalog, unfortunately.

On a more positive note, a significant and exciting catalog refresh is coming up, and will be announced soon. Stay tuned! 🤫

As usual, we want to sincerely thank every one of you, Sherlock users, for your patience when things break, your extraordinary motivation and your continuous support. We’re proud of supporting your amazing work, and Sherlock simply wouldn’t exist without you.

Happy computing and don’t hesitate to reach out if you have any questions!